2020 Vision: Documentary Filmmaking in a Global Pandemic

New Day Member-Owner Cheryl Green on the set of TBI & My Longest Ride

The weirdest year of our lifetime has hit its twelfth month. It is a good time to reflect on pandemic-plagued, economy-busted, politically-polarized 2020. What did you lose? What did you gain? How did you accommodate the world’s bizarre conditions?

When these questions were put to New Day filmmakers some surprising – even inspiring – answers emerged. While precautions prevailed over productivity and making movies slowed, creativity didn’t cease. People who devote their lives to telling stories for the betterment of society don’t let a pandemic stop them.

From production to post-production and distribution, members of New Day found new ways to ply their craft.

Production

TBI & My Longest Ride

Cheryl Green (Who Am I To Stop It) started a short doc in 2019 about Karl, a man with a severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) and his quest to heal himself when conventional medicine and insurance shortcomings left him high and dry. The project, TBI & My Longest Ride, was on hold for some time, to Karl’s dismay. The filmmaker finally got her work back on track again just before the Coronavirus pandemic was declared.

“It had been hard enough to schedule interviews with [the] medical experts Karl wanted to appear in the film. But once it was clear we could not film his acupuncture or speech therapy, there was suddenly no point (in my mind) to interview the experts.”

Cheryl explains that she usually has a practice of not interviewing medical experts when making films that feature disabled people. She was willing to make an exception this time since it was Karl’s desire to include medical practitioners, but after much negotiation, he agreed to focus the film solely on his own story.

“I never speak to experts because their stories and their fact-heavy interviews sometimes inadvertently distract from the subjects' agency. Describing the patient narrative takes time away from subjects describing their own human narrative.”

The filmmaker recently completed production, and is pleased with the direction it took. The project was funded by the Regional Arts & Culture Council.

For Cheryl, a highly politicized disabled documentarian, it is important who gets to tell stories of disability. “I'm deeply moved by the story being about Karl's journey and his family as opposed to medical experts explaining the value of the work they do for him. Without this change prompted by the pandemic, we wouldn’t have had the space for so much of Karl’s internal life that now is in the film.”

Up For Debate

For three years, Judy Lieff (Deaf Jam) has been following middle and high school students engaged with the New York City Urban Debate League. Much of her filming involved large groups of students gathered for tournaments.

“After participating in a couple of high profile pitching forums, I finally received a bit of grant money this past March.” Unfortunately, the day New York City shut down was the day the award ceremony and press roll out were supposed to take place. April was to be the last month of production and final scenes for the film. Instead, Spring became “a scramble to figure out income, business loans, and a new world of one Zoom meeting after another.”

Judy observes, “As artists, we naturally adapt to circumstances and find creative solutions to obstacles. But, being in a pandemic and riding the political turmoil of the time has taken a lot of wind out of my sails.” Judy is juggling parenting, teaching, and freelance filmmaking, which she says has taken much more of her energy and focus than she could have imagined.

As production shut down, Judy tried capturing the Zoom world of her subjects. She explains, “That only goes so far when the energy of the subject matter requires in-person gathering.” Comparing this effort with her verite style film in Deaf Jam, she says “[that] production was much more immediate and less self-conscious. I had regular in-person meetings with a co-producer which helped facilitate our timeline for finishing.”

Pandemic precautions have forced Judy to work solo. “I live with someone who has a compromised immune system. So, I have not gone back to working on any in-person productions.”

Judy laments falling behind in her production schedule with her current project, but says she is trying to be okay with that. Priorities shift when one's livelihood and health are in jeopardy.

For Judy, being a member of a filmmaking cooperative is a source of strength. “Being a part of New Day has been a blessing. I believe and trust that we all have each other's back. And that keeps me going.”

Post-production

Our Daughters

Chithra Jeyaram (Foreign Puzzle) found a silver lining in the pandemic-imposed conditions. She was working on Our Daughters, a documentary about open adoption from the perspective of an immigrant family in the US. The project was selected for the Independent Filmmaker Project (IFP) documentary lab, Sheffield Doc Fest Meet Market, and subsequently IFP Forum.

Typically, the IFP Lab is a five-day event that takes place in Brooklyn, NY, and the Sheffield MeetMarket happens each year in Sheffield, U.K. This year, due to the coronavirus, all screenings were virtual, and formal meetings were conducted over Zoom. While what transpires at these meetings is important, Chithra notes, “The real stuff happens when one is waiting for coffee, walking to the subway, grabbing lunch or over drinks at the post-event happy hour.”

That type of connection and engagement was missing. Zoom interaction replaced face-to-face exchanges, leaving Chithra to observe, “The presentations on Zoom are often prolonged monologues.”

Despite Zoom fatigue, Chithra got valuable feedback, finding the industry meet-and-greets beneficial. “Instead of jostling in a crowded room hoping to flag someone down for a quick conversation, the one-on-ones actually felt like one on ones.”

This helped Chithra feel more relaxed. “It felt more of a level playing field. You were in that person’s personal space.” Chithra chafes against the artificial nature of the “hierarchy and separation” when an “industry expert” counsels a filmmaker. But this time, to hear an authority offer a preemptive apology that her 10-month-old might enter the Zoom frame was “disarming.”

Distribution

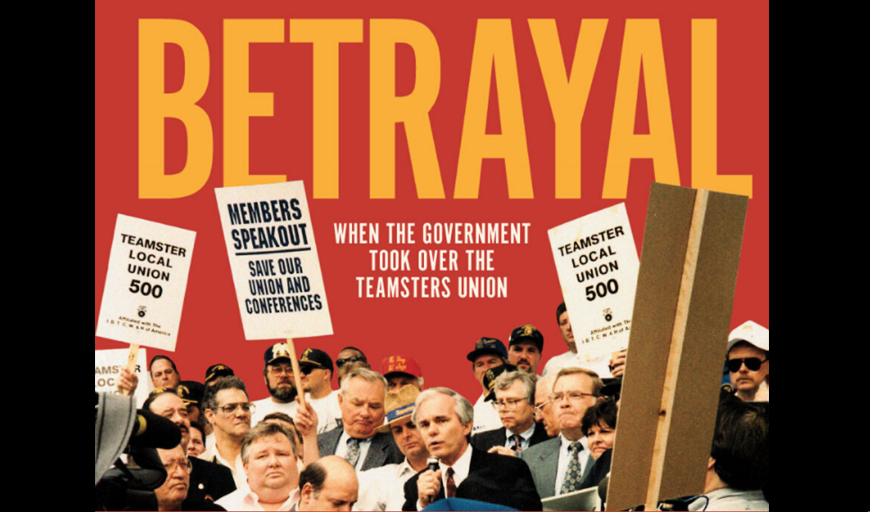

George Bogdanich (Betrayal: When the Government Took Over the Teamsters Union) was eagerly awaiting the screening of his documentary at October’s Workers Unite Film Festival in New York City. His film was being featured and he was going to speak on a panel. Despite New York's success in limiting the spread of Covid-19, the theatrical option at Cinema Village was replaced with a virtual festival.

This proved to be a thinly disguised blessing. The online platform enabled the festival to reach a much wider national audience of union activists and labor professors. The Zoom panel had a lively Q&A session moderated by Professor Dan Graff who heads Labor Studies at Notre Dame and who appeared in the film.

Already planning his next film, George and his collaborators are grappling with the discovery that mask-wearing characters present not only an aesthetic issue, but impose a barrier for the audience to see interactions that “would be crucial to the film.”

Gathr Films

New Day member Laurel Chiten (The Jew in the Lotus and Twitch and Shout) also doubles as the Head of Acquisitions for Gathr Films. In that capacity she has issued a pitch to fellow moviemakers. “In April, when the theaters were closing,” she wrote, “Gathr created Gathr At Home, a virtual screening platform.”

Born of the frustration of not being able to present work in person, Gathr At Home’s online solution offers several options. A new film can use the platform to create a virtual world premiere, while older work can develop a new revenue stream. The system also can provide private screenings targeted to specific audiences, like educators.

Each screening is set up as a live customized event with all viewers watching the film at the same time, as if in a movie theatre. “Except,” Laurel notes, “you can now have a limitless global audience all watching together.”

In early March, Rick Goldsmith (whose films include Tell the Truth and Run: George Seldes and the American Press, Everyday Heroes, and Mind/Game: The Unquiet Journey of Chamique Holdsclaw) flew to Chicago to interview two investigative reporters for his doc-in-progress, Stripped for Parts: American Journalism at the Crossroads. By the time he returned to California and got the footage into his editing system, his state and most of the country was on lockdown. The veteran filmmaker suddenly faced multiple unforeseen obstacles. Travel became impractical, as did capturing (maskless) footage.

Rick wrestled with the reality of having a large unmet production and post-production budget. Funding opportunities had dried up. “I had holes in my story which I needed to plug, but no way to do that.” He stumbled through the next seven months, “editing with what I had in the can, but it was a continuous slog.”

In October came his “aha” moment. “I had a brainstorm that might (might!) save the project.” He is now exploring reworking the film and distributing it as a podcast series, instead.

Rick is excited by the possibilities of gathering audio-only production more quickly, reliably and inexpensively. He’s also excited about reaching new and younger audiences, and developing new skills with a more personal approach.

“Not necessarily easy for this old dog, but I welcome the challenge. I am re-energized. A door shuts, a window opens.”