Intersectional and Interdependent: Disability Films that Embody Complexity

As we celebrate Disability Awareness Month this October, we recognize the many gains the Disability Rights movement has made over the past four decades.

Through grass-roots protests and political campaigns, activists helped put in motion legislation guaranteeing equal access under the law to jobs, schools, transportation, public spaces, housing and attendant care. Later victories included the de-institutionalization of hundreds of thousands of people with disabilities under the Olmsted Decision. While these gains have improved the quality of life for many, the Disability Rights movement has left a number of “cliffhangers,” as Patty Berne, a leader in the Disability Justice movement, puts it.

The focus on single-issue rights and highlighting of wheelchairs as the primary symbol of disability have unintentionally left many behind. By ignoring the influence of race, class, gender, and sexuality on disability, we overlook the complexity and needs of the broader disability community. Similarly, the exclusive focus on mobility impairments has meant that bridges have not always been built with members of our extended communities—such as people with mental health disabilities, or who experience chronic pain, or who are blind or Deaf.

In response to these needs, the Disability Justice movement has arisen with people of color at the forefront, articulating a new framework that is intersectional and interdependent. New Day's catalogue offers a collection of films that expand our understanding of disability.

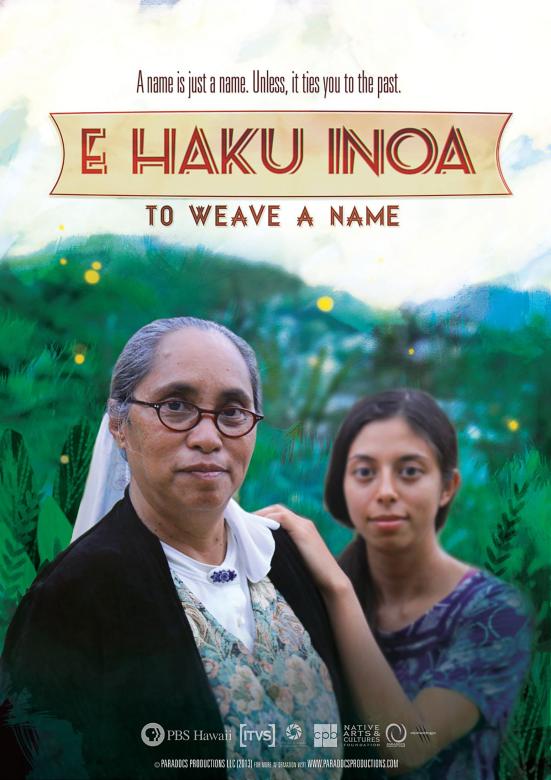

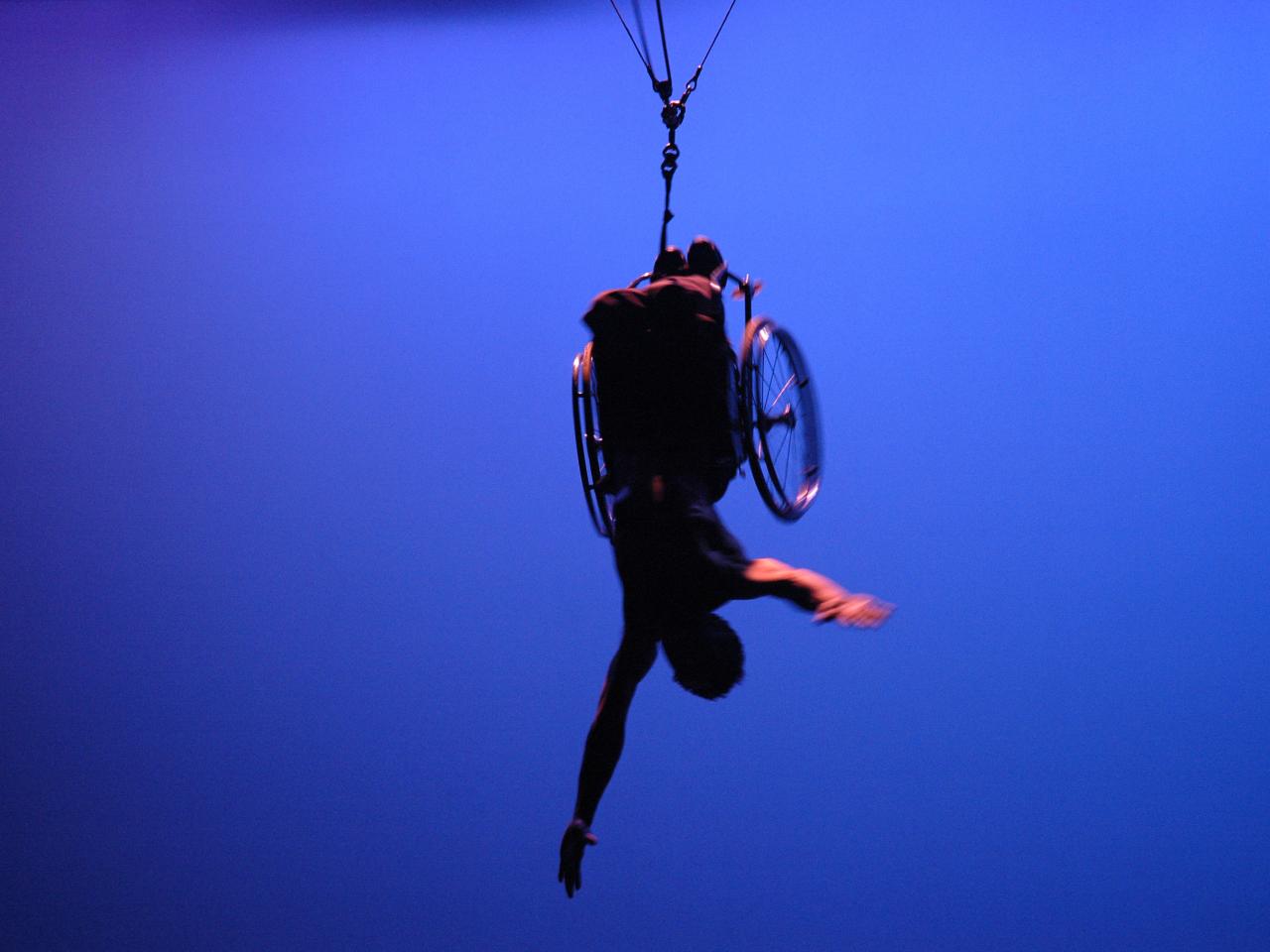

Five films in particular explore the intricate intersection between disability and race: Sins Invalid, E Haku Inoa: To Weave a Name, Making Noise in Silence, Mind/Game, and When I Came Home. Sins Invalid: An Unshamed Claim to Beauty documents a Bay Area performance project that highlights artists with disabilities who are queer, gender non-conforming, and people of color, and who create work around themes of disability, sexuality, and social justice.

Director Patty Berne, poet Leroy Moore, and a dozen other artists share their intimate and beautiful process and work, offering an entryway into the absurdly taboo topic of sexuality and disability.

When filmmaker Christen Marquez was born, her mother, a kumu hula (master hula practitioner), gave her a Hawaiian name that was over sixty letters. Eight years later, her mother was diagnosed with schizophrenia and Christen and her siblings were taken away from her. E Haku Inoa: To Weave a Name tells of Christen’s return to Hawaii, and is an elegant depiction of how the act of sharing indigenous knowledge can play a healing role in restoring otherwise estranged relationships. Marquez reflects, ”There is a stigma of sickness that is imported into indigenous communities and although there are many health problems that exist in indigenous communities, I wonder if some diagnoses aren't a fulfillment of an expectation. Many people don't need a diagnosis; they just need someone to help them heal.”

Director/producer Mina Son explores the richness and complexities of Deaf culture in Making Noise in Silence, through the perspective of two Korean high school students who attend the California School for the Deaf, Fremont. Born and raised in South Korea, Jeongin Mun and Min Wook Cho have strong ties to their Korean heritage and learned Korean as their first language. However, what separates Jeongin and Min Wook from most children of immigrant families is that they are also deaf.

Filmmaker Mina Son shares: “Deaf immigrants face many of the same challenges people with multiple identities face. Navigating multiple languages, cultures, and histories can be overwhelming, especially for a young person who is still trying to understand who they are and where they belong.”

Mind/Game: The Unquiet Journey of Chamique Holdsclaw, by Academy Award-nominated director Rick Goldsmith, is the portrait of a Black woman with a mental illness. Chamique Holdsclaw is a 3-time NCAA champ and No.1 draft pick in the WNBA from Astoria, Queens— sometimes called “the female Michael Jordan.” With the help of narrator Glenn Close, Mind/Game intimately chronicles her athletic accomplishments, personal setbacks, and her decision—despite public stigma— to become an outspoken mental health advocate.

Dan Lohaus’ powerful film, When I Came Home, follows the struggles of Herold Noel, an African-American Iraq war veteran who becomes homeless in New York City after returning from combat with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Focusing on Herold's struggle with the Veterans Administration and city agencies to find the help he needs, When I Came Home reveals a failing system and exposes the "second war" that many veterans must fight after they return home from war.

These films reveal the multiple layers of struggle that disabled people of color must navigate every day, with insight into the human drive toward beauty, empowerment and connection. What is it like to learn American Sign Language as a new immigrant to the US? What are the cultural misunderstandings between the western medical model and indigenous ways of knowing? What does radical embodiment at the intersection of multiple identities look and feel like? How do people heal from the devastation of war when they come home to find a culture that doesn’t include them?

New Day hopes these films will illuminate the perspectives of those who have typically been at the margins of the Disability Rights movement, whose daily existence is the embodiment of intersectional activism.

See our whole collection of disability films.